The Sheraton and the Cart: Eating Ful and Ta’amiya – Between Luxury, Tradition and Reinvention

I remember tasting ful at the Sheraton in the 1970s, a luxury setting for Egypt’s most ordinary meal. But I also recall the carts on the street, and more recently Zooba’s reinvention, each reflecting how food carries both continuity and change in Egyptian identity.

In 1970s Cairo, the Sheraton Hotel -- designed by architect Mohamed Ranzy Omar stood as a beacon of luxury, a newly built tower on the Nile Corniche projecting the city’s aspirations toward modernity. For me, however, its most memorable feature was not its casino, restaurants, or marble lobby, but a corner devoted to something far more ordinary: ful and ta’amiya. My uncle Osama used to take me and my brother, and the experience always struck me as extraordinary—eating the most traditional of Egyptian foods in one of the city’s most opulent settings.

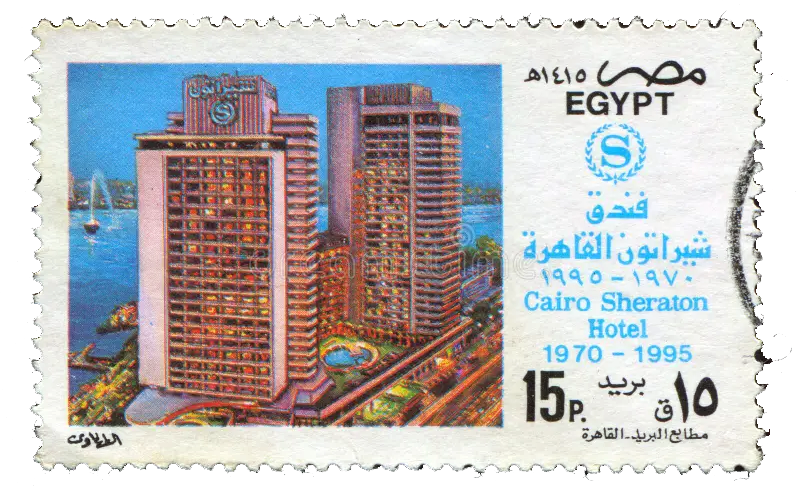

Sheraton Hotel. Cairo

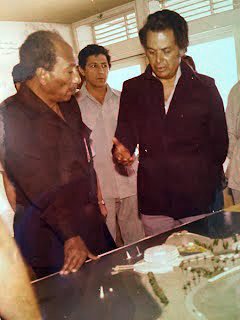

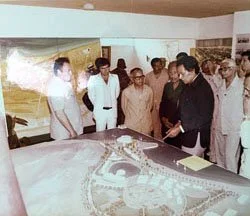

Mohamed Ramzy Omar presenting to Anwar Sadat

Driving across from the Hotel' Side Entrance

Hotel Side Entrance

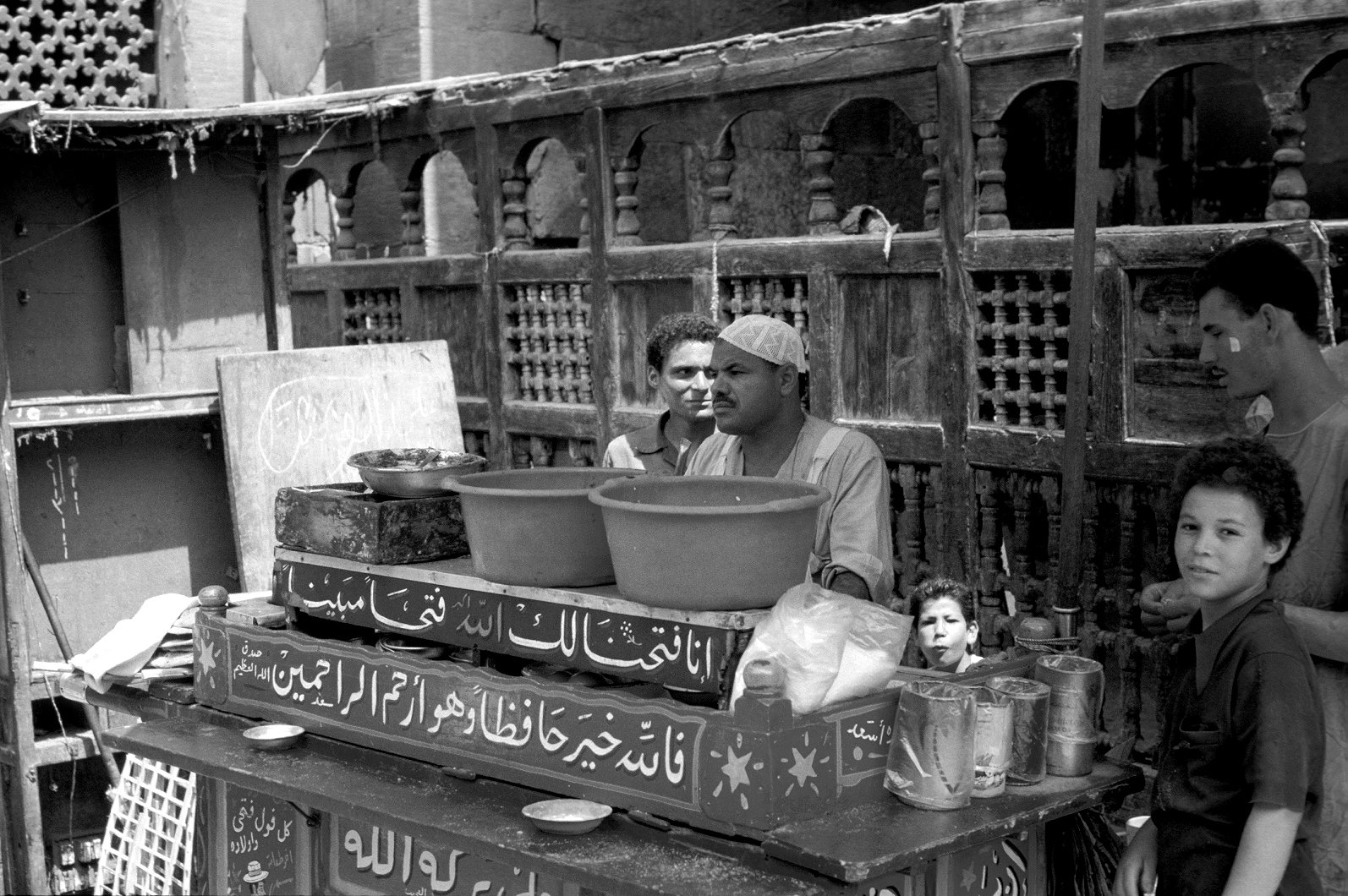

A Traditional Egyptian Food Setup

Entrance to the Sheraton Cinema

Globalizing Ful & Ta’amiya

If the Sheraton represented ful’s unlikely elevation, and the carts its enduring tradition, then Zooba offered yet another reimagining—one that sought to globalize Egyptian street food altogether. Founded in 2012 by Chris Khalifa with chef Moustafa El Refaey, Zooba began in Zamalek on July 26th Street, later opening branches in Maadi and other neighborhoods. Its mission was clear: to take Egypt’s everyday staples—ta’amiya, koshary, ful, hawawshi, liver sandwiches—and present them in a fresh, design-savvy way. Unlike the gritty eateries of Say’yida Zeinab or the gleaming Sheraton counters, Zooba’s interiors were colorful, playful, and modern, filled with eclectic graphics, Arabic calligraphy, and nods to Cairo’s street culture

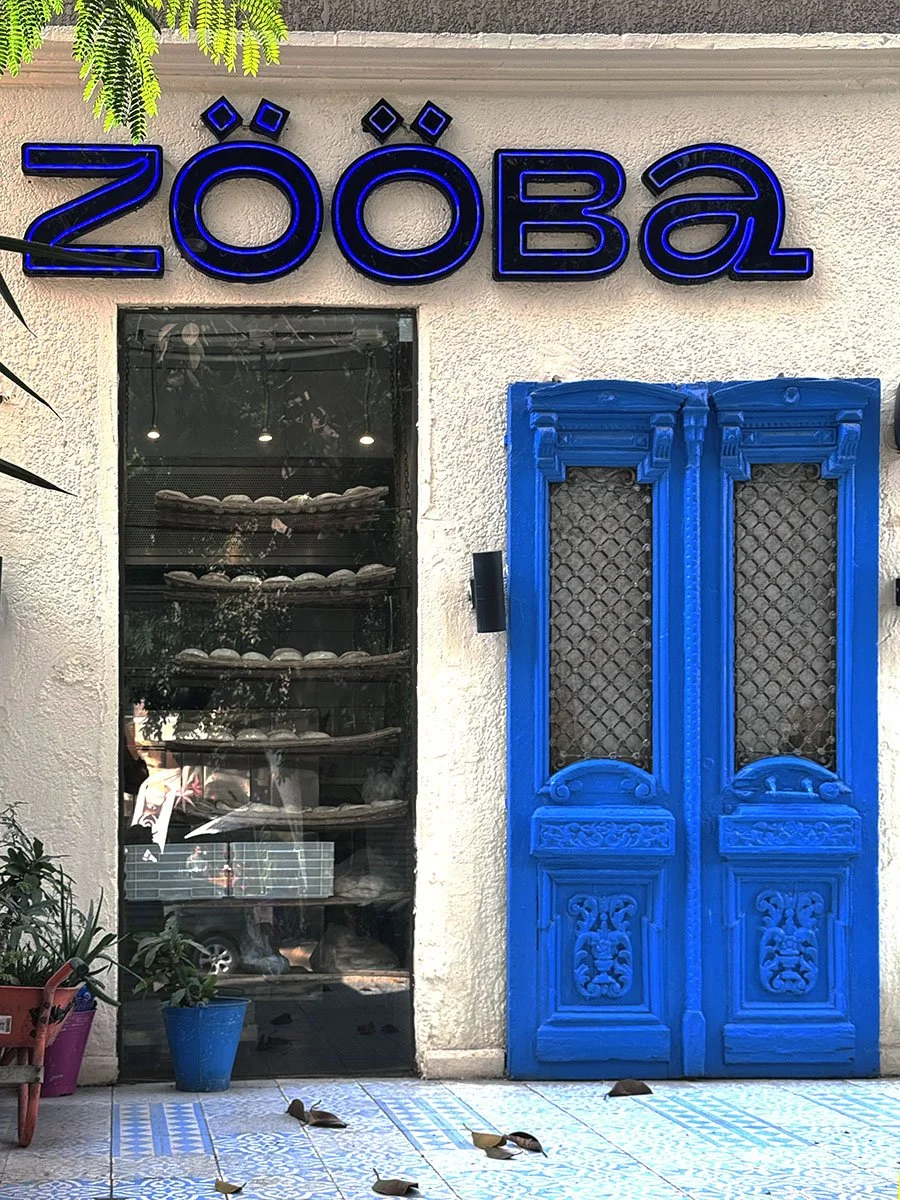

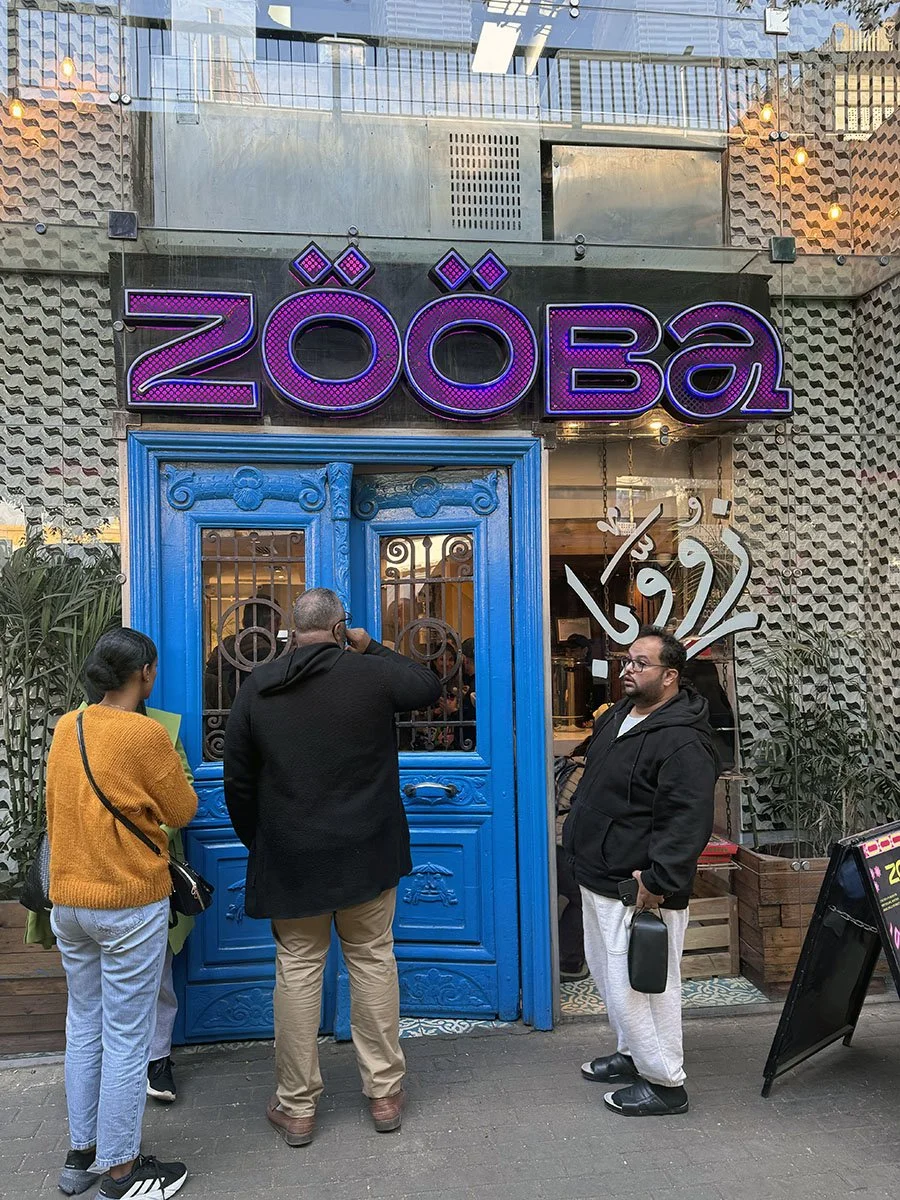

Zooba. Zamalek

Zooba. Zamalek

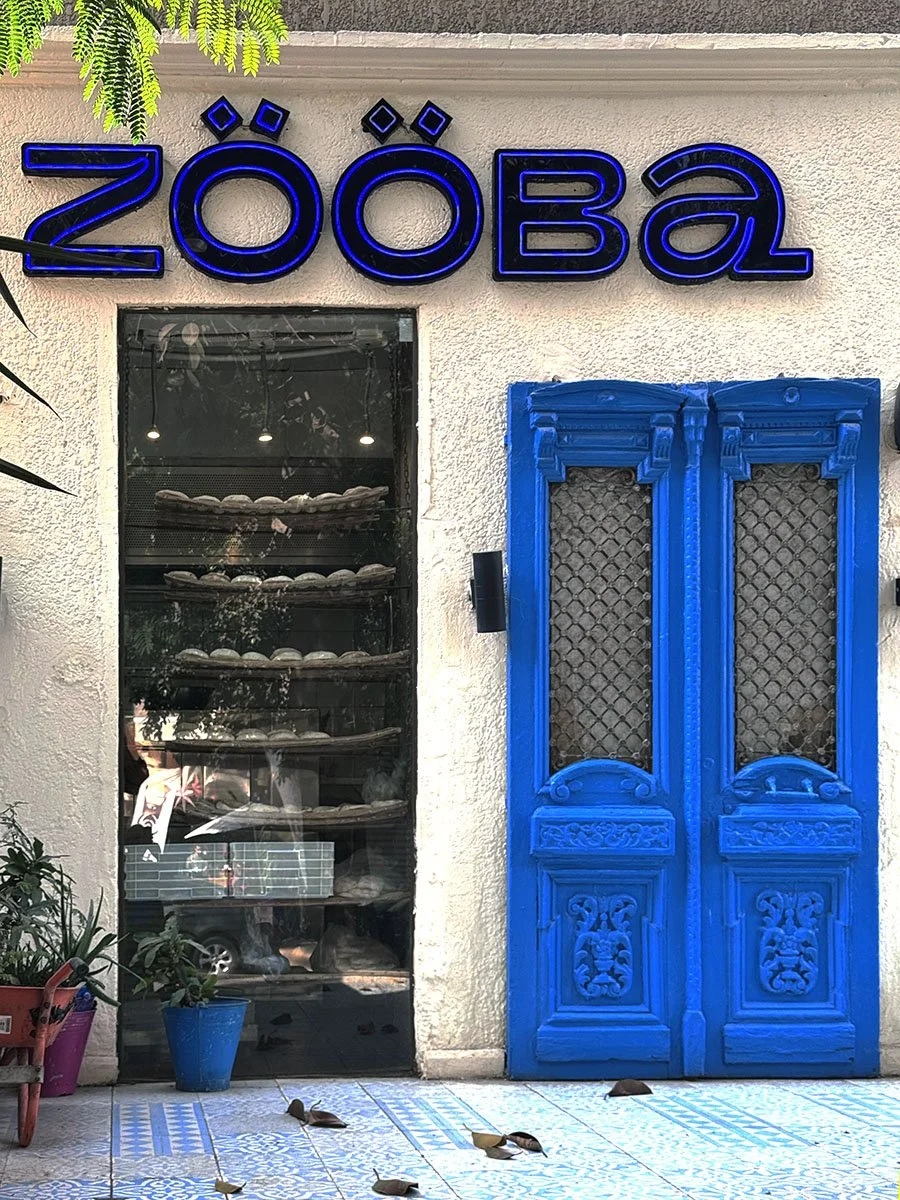

Zooba Maadi

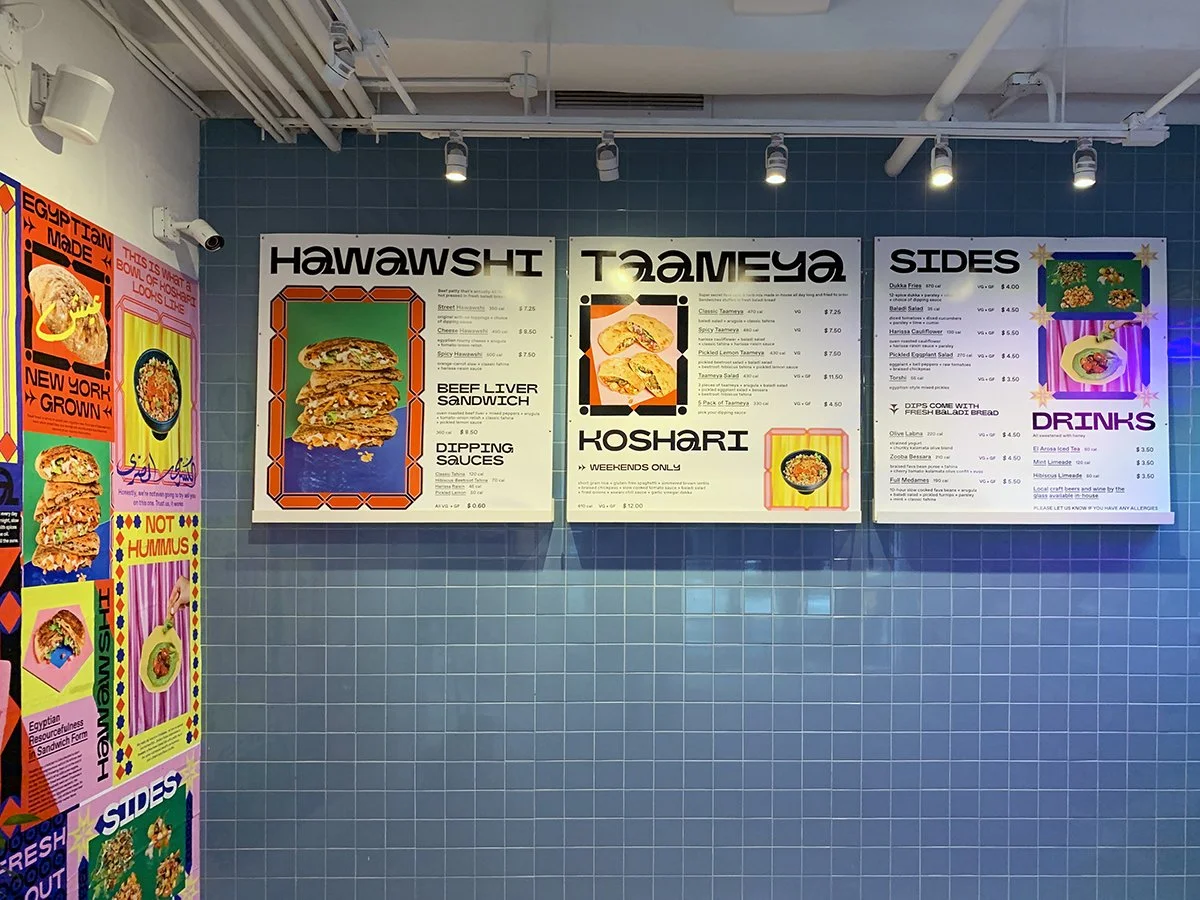

When Zooba entered the New York dining scene in 2019, opening a branch in Nolita, it seemed poised to make Egyptian food part of the city’s cosmopolitan tapestry. Its Nolita space was bright and inviting, echoing its Cairo design, with colorful signage and playful references to Egyptian street life. For the first time, dishes like koshary and hawawshi were presented not as exotic curiosities but as centerpieces of a contemporary dining concept. Reviews were positive; critics praised Zooba for maintaining authenticity while giving Egyptian cuisine a modern polish. As for me seeing the familiar signage in lower Manhattan felt like encountering a piece of ‘home’ abroad. The economics of Manhattan dining—high rents, intense competition, and the disruptions of the COVID-19 pandemic—made it difficult to sustain. Pricing was another challenge: the affordability central to Egyptian street food could not be reconciled with New York’s costs. By 2023, Zooba had closed its Nolita branch, a reminder that even the best ideas struggle in one of the world’s toughest restaurant markets.