Between Two Mosques: Urban Life, Memory, and the Sultan Hassan/Rifa’i Passage

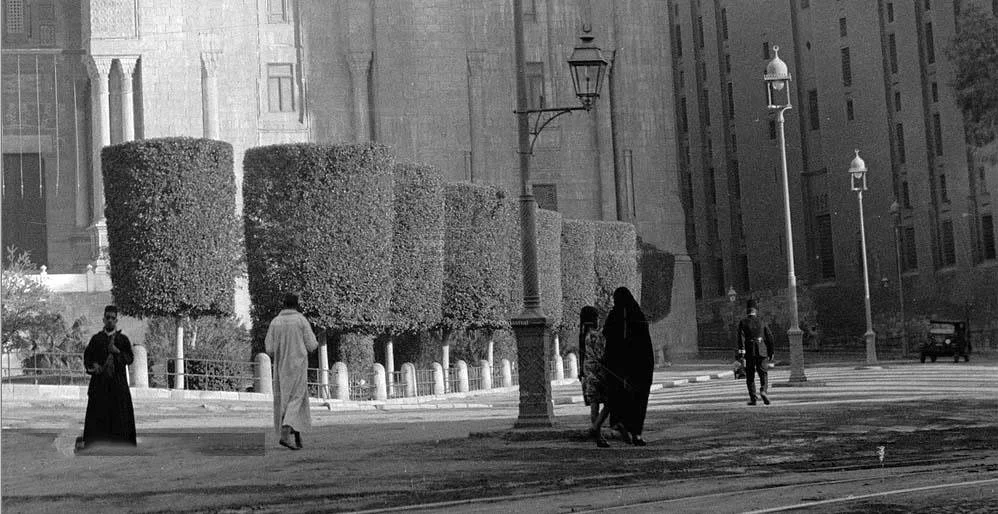

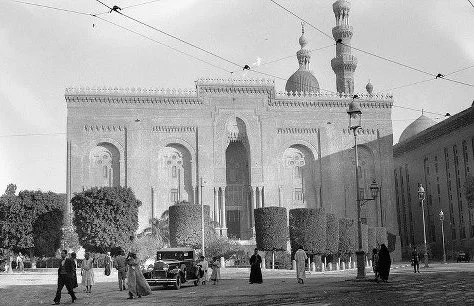

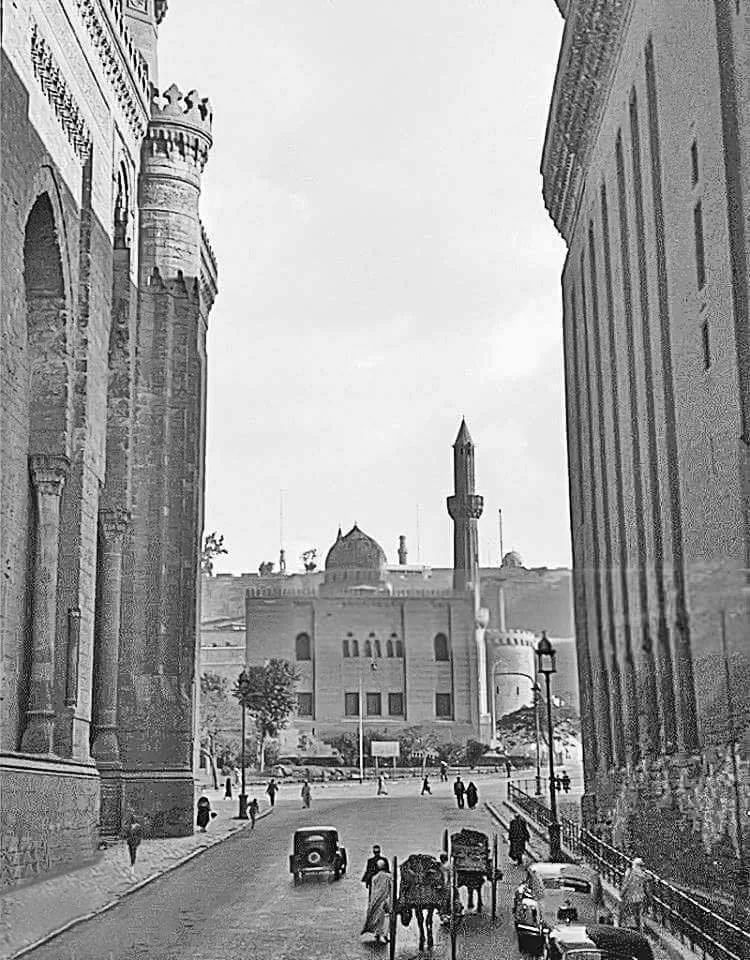

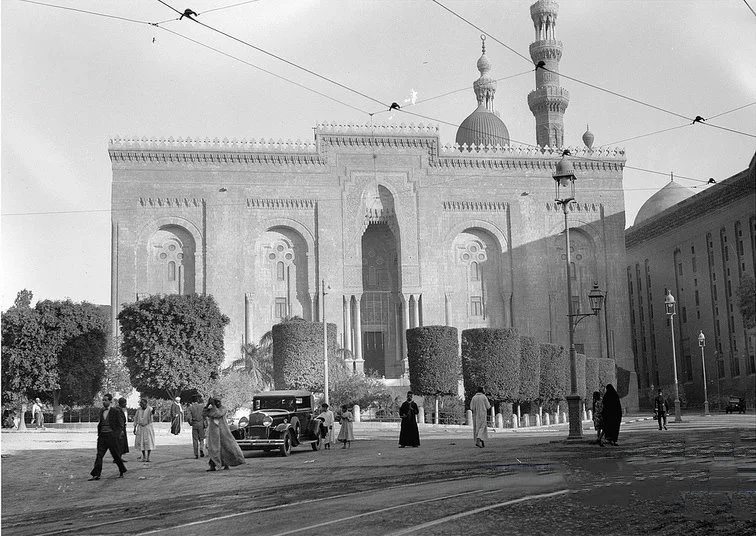

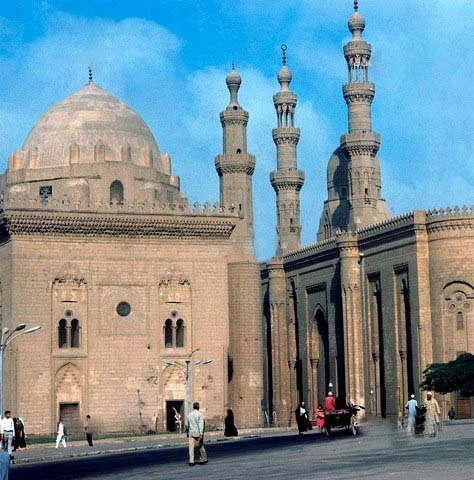

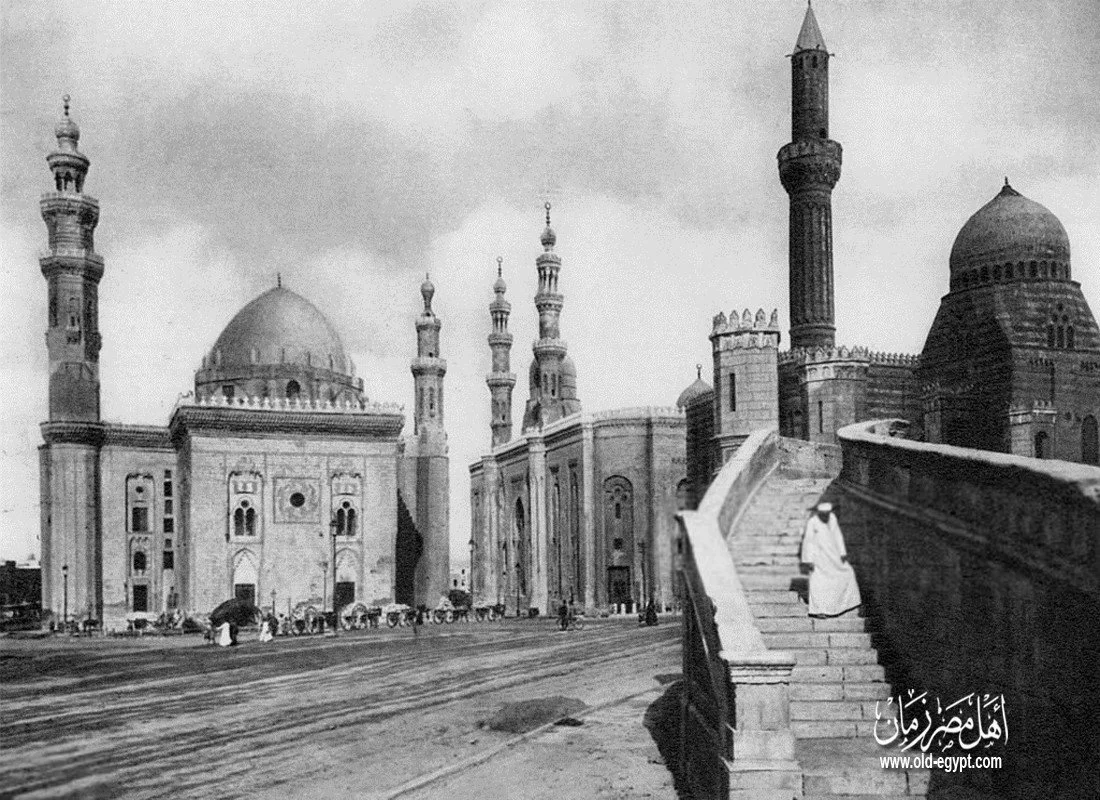

Below the Cairo Citadel, adjacent to Salah al-Din Square, two monumental mosques face each other in silent grandeur. On one side rises the 14th-century Madrasa and Mosque of Sultan Hassan, one of the most impressive achievements of Mamluk architecture; on the other, the Rifa‘i Mosque, completed in 1912 in a neo-Mamluk style to house royal tombs and to project modern state power. Between them lies a narrow passage, an urban corridor whose history reflects Cairo’s transformations and the shifting politics of its public spaces

The Passage

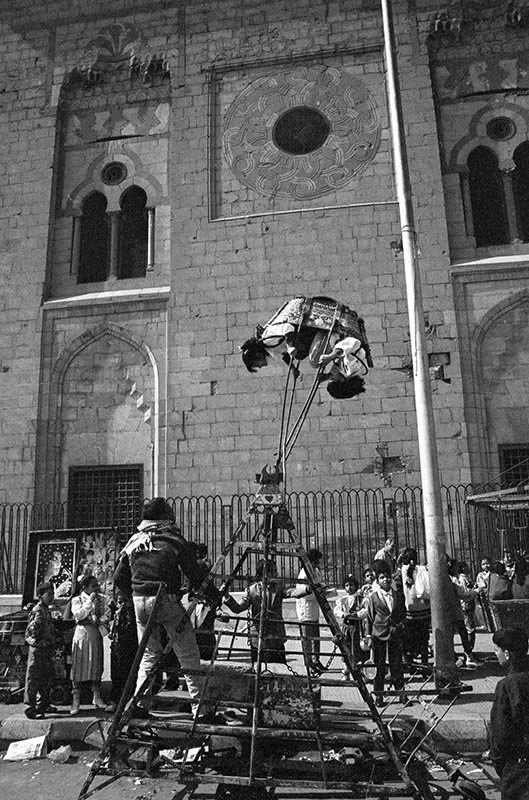

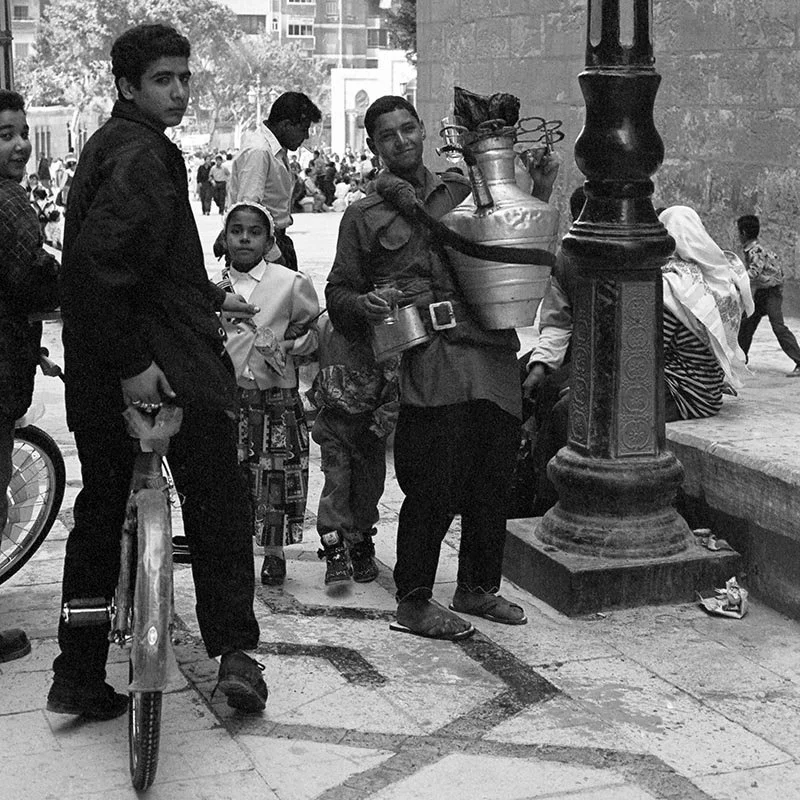

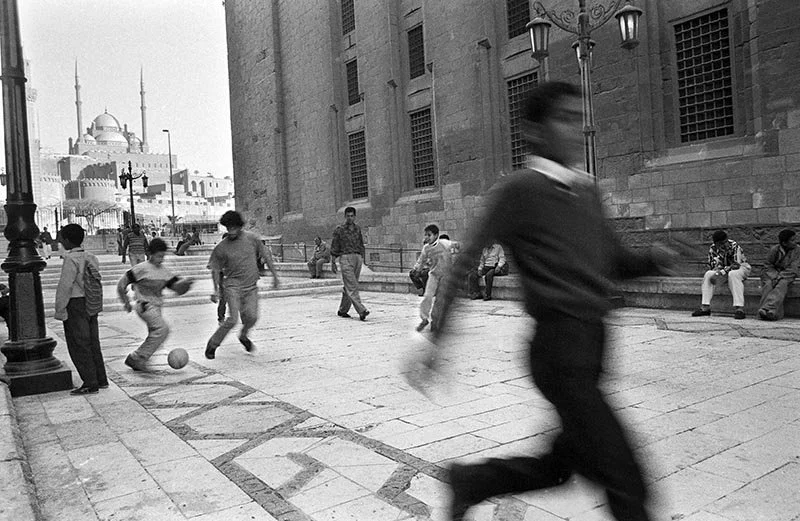

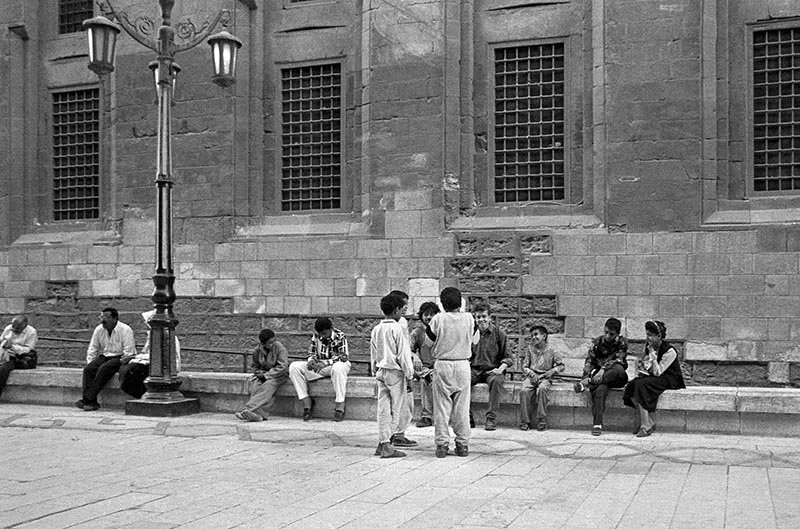

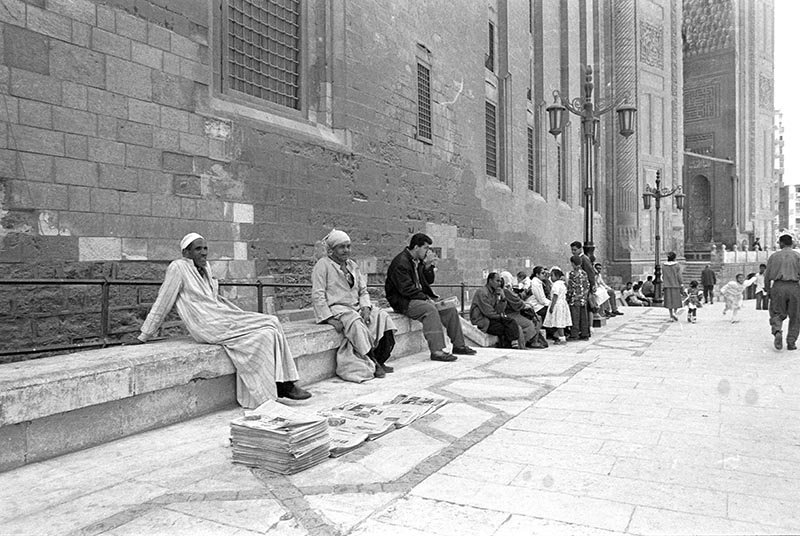

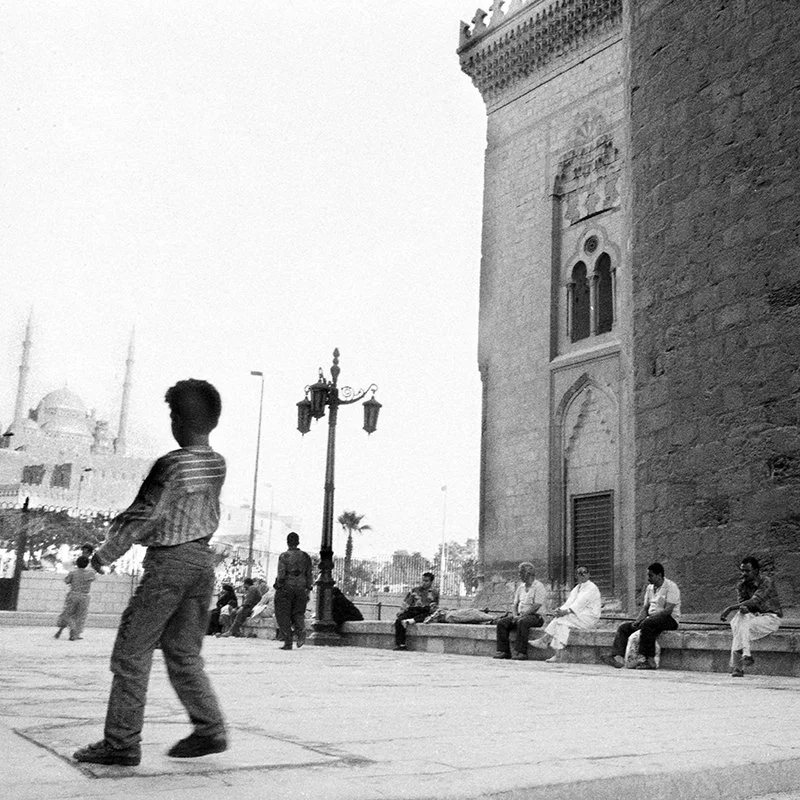

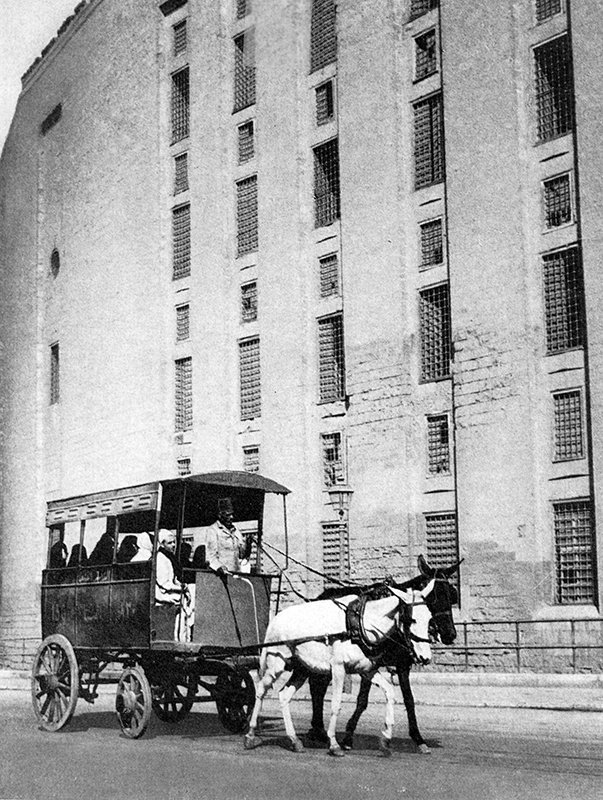

For decades, vehicles funneled between the Sultan Hassan and Rifa‘i mosques, the passage effectively serving as a continuation of the boulevard. By the 1980s, however, Department of Antiquity officials and urban planners deemed the juxtaposition of monumental mosques and rumbling traffic unseemly. With tourism now a central pillar of Egypt’s economy, they decided to close the passage to vehicles and transform it into a pedestrian zone. The aim was to monumentalize the space, turning it into a heritage corridor fit for tourists visiting Cairo’s medieval monuments. Yet what transpired defied these expectations. Instead of a sanitized tourist walkway, the space became a living communal square, appropriated by residents of the surrounding neighborhoods and animated by their daily activities.

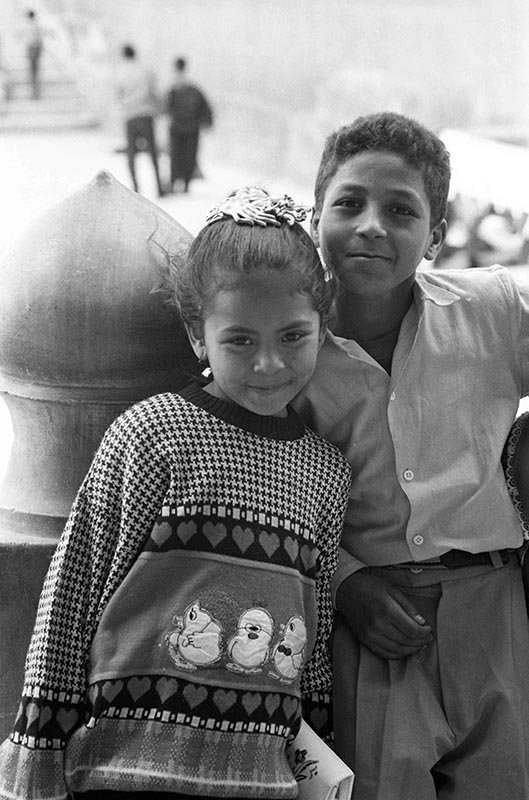

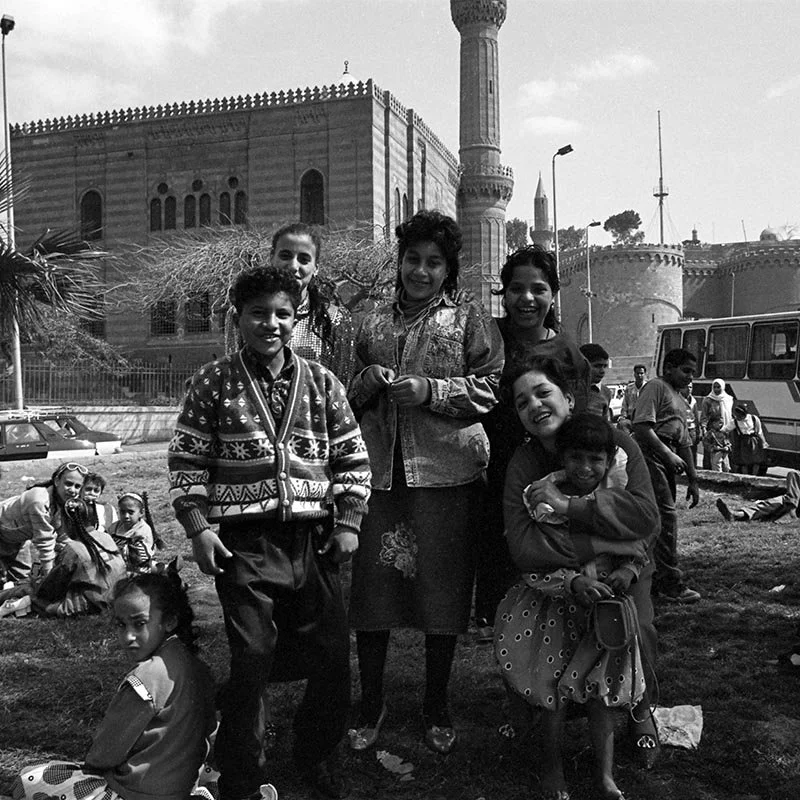

The People

A Zaffa

One afternoon I witnessed a zaffa—a traditional Egyptian wedding procession—making its way through the corridor. The bride and groom, encircled by singing and dancing relatives, transformed the space into a wedding hall under open skies. The moment crystallized how the pedestrianization of the passage allowed deeply rooted cultural traditions to flourish in the public realm, outside the confines of costly hotels or wedding halls.

By the late 1990s, the state reasserted control. In 1997, after my fieldwork had concluded, the Mohamed Ali Street entrance was permanently closed with gates, while at the Salah al-Din Square end a ticket booth was installed for tourists. Egyptians could still enter without charge, but the loss of the through-route meant few had reason to linger. The corridor ceased to function as a living passage and reverted to a sterile heritage site. Only on Fridays, when both mosques opened for prayers, were the gates briefly unlocked to allow worshippers through.

Qala'a Square

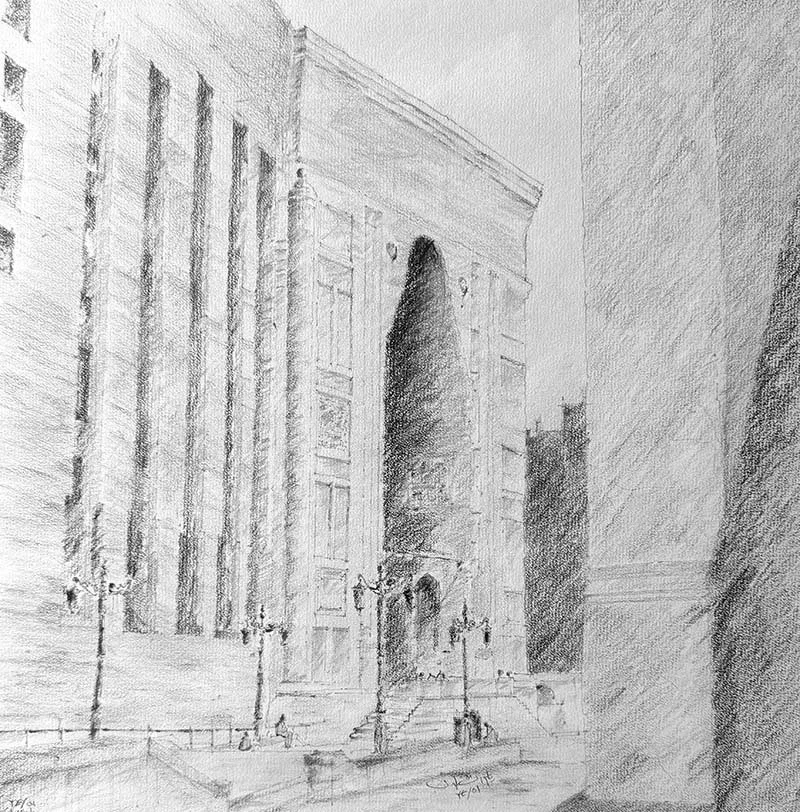

Ticketing booth at the passage entrance

Mohamed Ali Street Entrance. Only open for Friday prayers

Shuttered gate following end of prayers

A severed connection to the community

Dead Passage

What once was a vibrant passage has been turned into a spectacle for tourists. Only on Friday’s do we get a glimpse of what once was there but now is no more

Looking back, the Sultan Hassan–Rifa‘i passage stands out as one of Cairo’s most extraordinary urban experiments. For a brief, fleeting moment, it showed how architecture and urban design could foster inclusivity, spontaneity, and joy. It became a civic stage where ordinary people enacted their lives against a monumental backdrop, transforming tourist space into lived space. Yet its fate also illustrates the disjuncture between people and the state in Egypt’s urban politics. Where residents saw opportunity, community, and life, authorities saw risk, nuisance, and threat.