Café Riche and the Making of Modern Cairo: Poetics, Literature and the Urban Life of Downtown

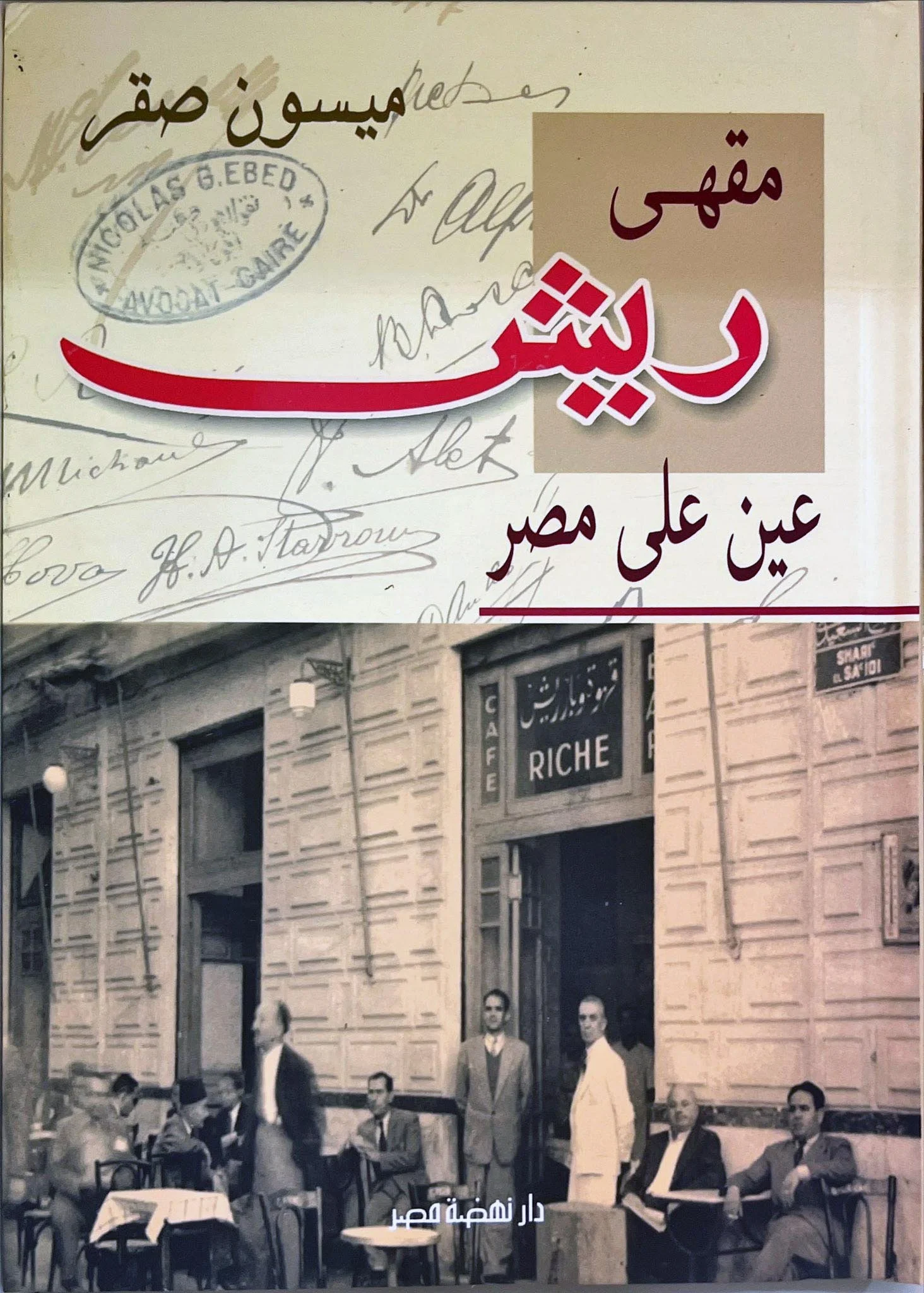

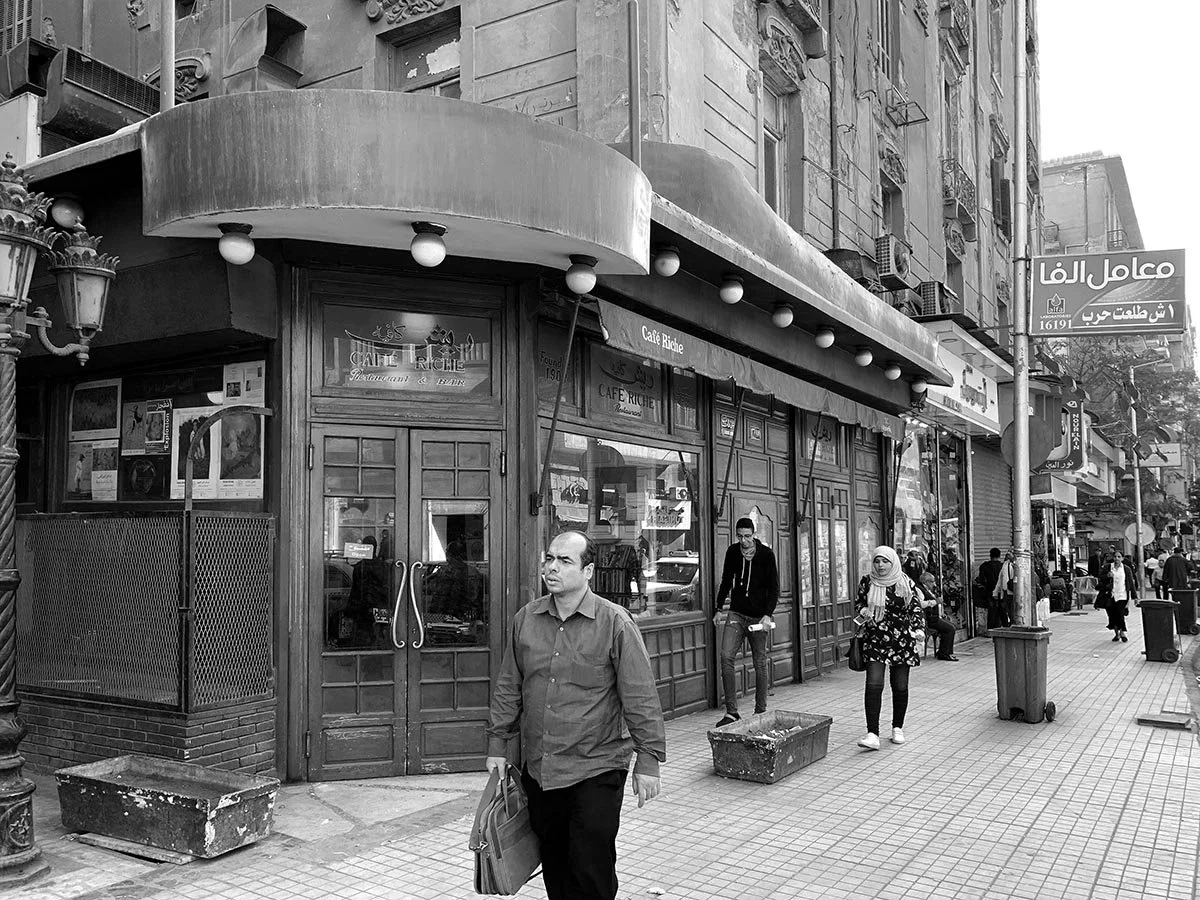

Café Riche’s history is inseparable from the modern history of Egypt itself. In the early decades of the 20th century, it was already recognized as a meeting point for activists during the 1919 nationalist uprising against British rule. Revolutionaries plotted at its tables; journalists wrote fiery columns; poets recited verses. Later, during the years leading up to the 1952 Revolution, a young Gamal Abdel Nasser was known to have sat here, discussing politics with fellow Free Officers, his future still uncertain. Writers, too, left their mark: Naguib Mahfouz, decades before winning the Nobel Prize, was a regular.

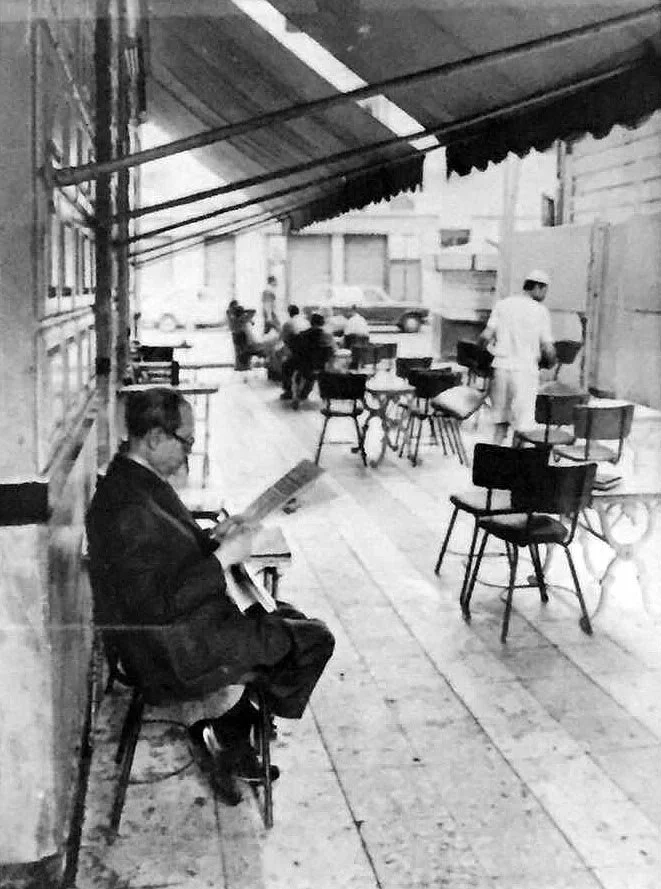

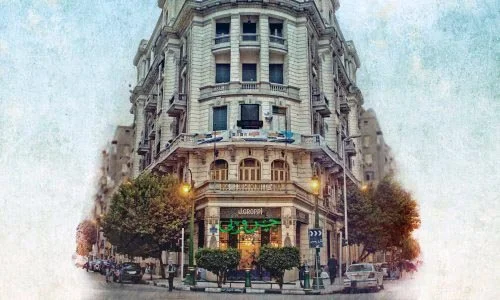

When I sit there today the clientele is mixed: a handful of locals, a few tourists, couples spending some time together. The outside passage where I once rested is gone, now folded into the interior, and the bustle of Talaat Harb presses in through the windows. Yet the photographs still line the walls, the furniture still recalls another era, and the weight of history remains palpable. Café Riche is both a functioning café and a monument — a place where one can still sense the overlapping layers of Cairo’s intellectual, political, and urban life.

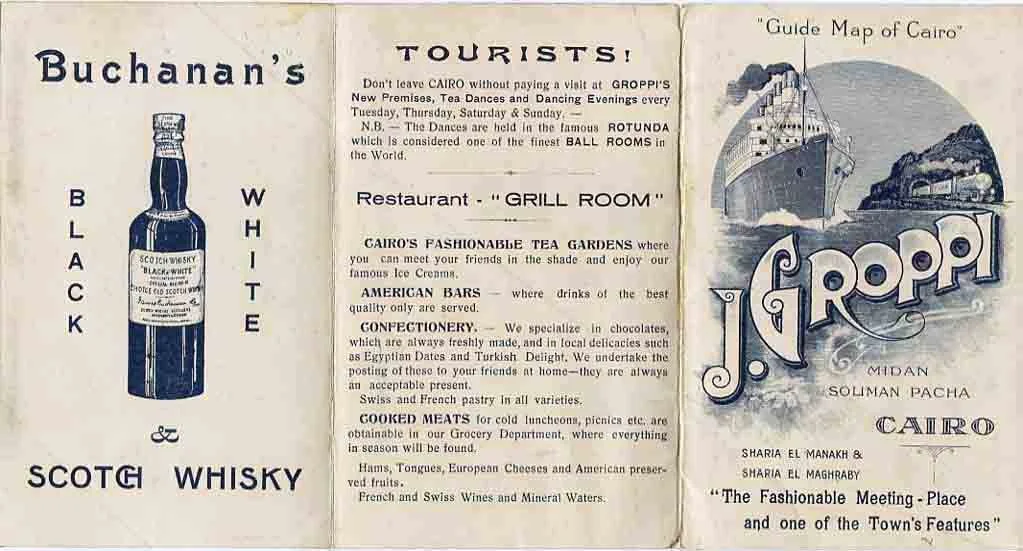

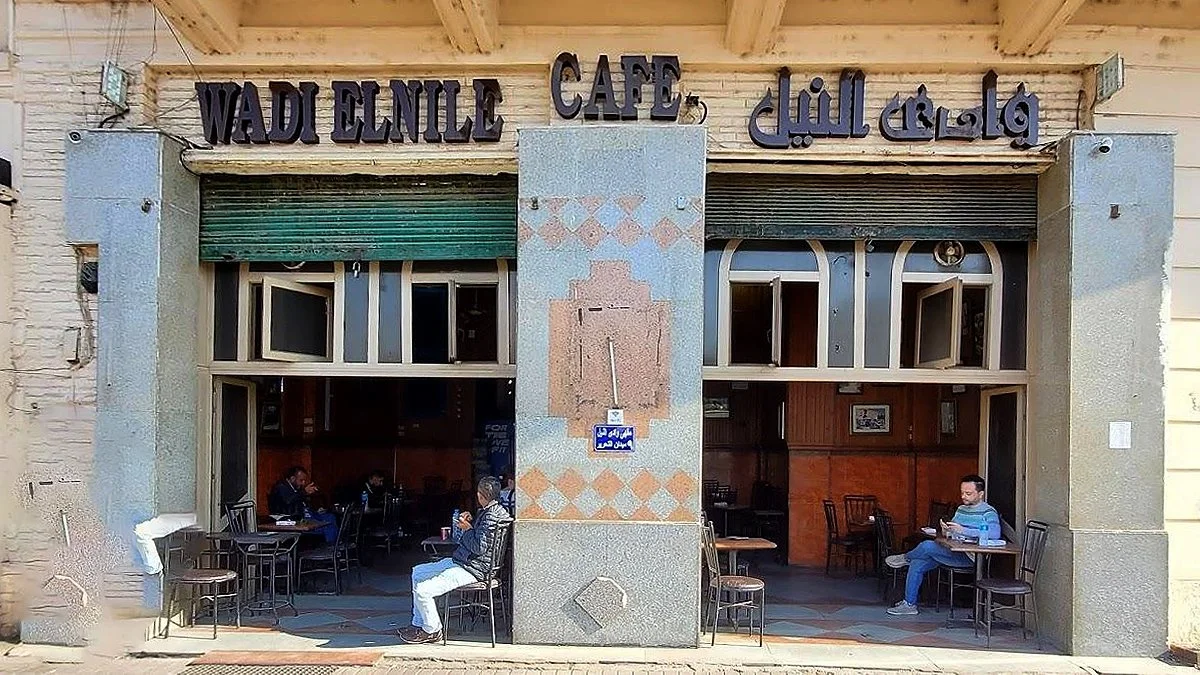

Café Riche is part of a wider constellation of downtown institutions that defined the area’s cultural life. Groppi, once the most famous patisseries in Cairo, stood nearby. There was another Groppi branch not far away, known as Groppi Garden, located just off Opera Square. Unlike the main shop, it featured an outdoor courtyard seating area, a place where one could linger in the open air. There was also the Café Americain, another downtown landmark, with its American-style cafeteria layout and bright atmosphere. Located near Talaat Harb Square, it was a place that carried its own cultural weight as a gathering spot for middle-class Cairenes. And of course facing Tahrir square was the Wadi Al-Nil Ahwa (now renamed to Tahrir Café).

Groppi

Groppi Menu

Groppi Garden

Groppi Garden

Groppi

Groppi

L'Americain

L'Americain

Wadi al-Nil Cafe

Wadi al-Nil Cafe