Cities We Carry Within Us: Cairo and the Landscape of Memory

Istanbul. Ara Güler

“A street might remind us of the sting of getting fired from a job; the sight of a particular bridge might bring back the loneliness of our youth. A city square might recall the bliss of a love affair; a dark alleyway might be a reminder of our political fears; an old coffeehouse might evoke the memory of our friends who have been jailed. And a sycamore tree might remind how we used to be poor”

This section introduces the reader to Cairo as an “index of emotional life,” where places embody memory and personal history. Inspired by Orhan Pamuk’s recollections of Istanbul, it situates the essays as fragments of a personal cartography, mapping Cairo through third places like cafés, cinemas, and restaurants.

Cairo. 1960s.

Cairo, Roma, Hong Kong: A Cinematic Cartography

Cairo 1984

Roma reveals how ordinary streets, homes, and routines accumulate memory and absorb historical rupture. The city is not a backdrop but an emotional archive, where the intimate and the political coexist. Watching Roma clarified my own experience of Cairo, where the most unremarkable places often hold the deepest weight of memory.

Ann Hui’s July Rhapsody portrays Hong Kong’s high-rise life as a quiet tension between confinement and longing, where everyday spaces absorb unspoken desires. Its depiction of urban density as both sustaining and restrictive mirrors a paradox deeply familiar in Cairo.

Last Tango in Paris treats the city as a space of anonymity and emotional drift rather than romance. This vision echoes Cairo as I experienced it—an everyday city that quietly absorbs solitude, desire, and inner turmoil.

The Dreamers reveals the city as a charged political terrain, where streets and interiors carry the promise of revolt and liberation. This sensibility resonates with Cairo, where moments of protest expose urban space as a stage for collective imagination rather than neutral infrastructure.

Mountains reflects on home as something fragile yet persistent amid gentrification and urban erasure. Its meditation on belonging and loss resonates strongly with Cairo, where rapidly transforming neighborhoods continually test what it means to remain present in place.

In the Mood for Love transforms cramped interiors and shared stairwells into spaces charged with longing and restraint. This intimate reading of the city resonates with Cairo, where proximity and density often intensify unspoken emotions rather than release them.

Three Colors: Blue frames the city as a quiet landscape of grief, where everyday spaces absorb loss and emotional withdrawal. Its restrained urban intimacy echoes Cairo as a place where personal sorrow often unfolds in silence amid the routines of city life.

Urban Memory and the Literary Imagination

“A building is not just concrete and stone. It is the lives of those who inhabit it, their hopes and defeats written into its walls

”

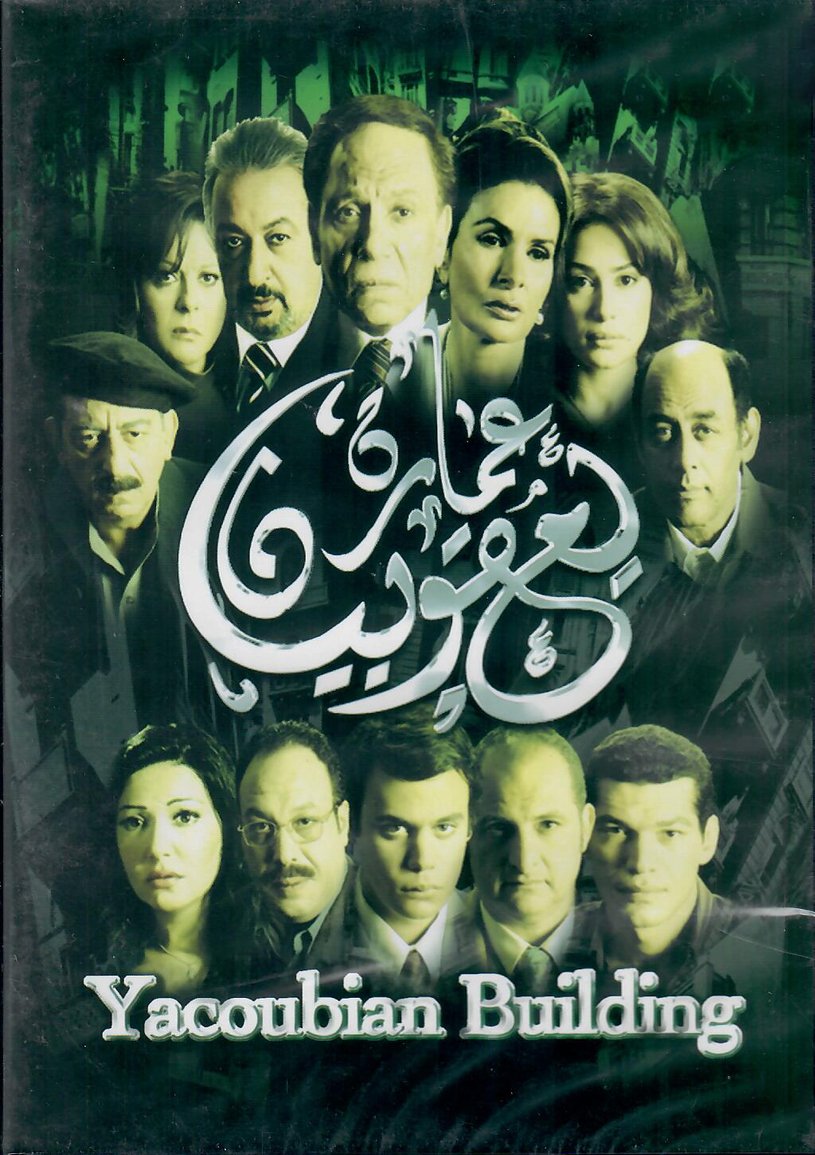

The Yacoubian Building shows how a single downtown apartment block can embody Cairo’s social and historical transformations. Through its architecture and inhabitants, the building becomes a microcosm of the city, where private lives intersect with broader forces of power and change. Reading it underscores how architecture itself can carry memory, condensing an entire city’s contradictions into one place.

In Austerlitz, the architecture of European stations and fortresses becomes a haunted repository of trauma. These spaces silently store what history suppresses, allowing memory to surface through walls, corridors, and ruins. This idea resonates with Cairo, where buildings and infrastructures often bear the invisible weight of personal and collective pasts.

In In Search of Lost Time, a church spire glimpsed from afar can unlock cascades of remembrance. Architecture becomes a catalyst for memory, collapsing time into a single moment of perception. I recognize this same dynamic in Cairo, where a familiar skyline or minaret can suddenly summon entire layers of lived past.

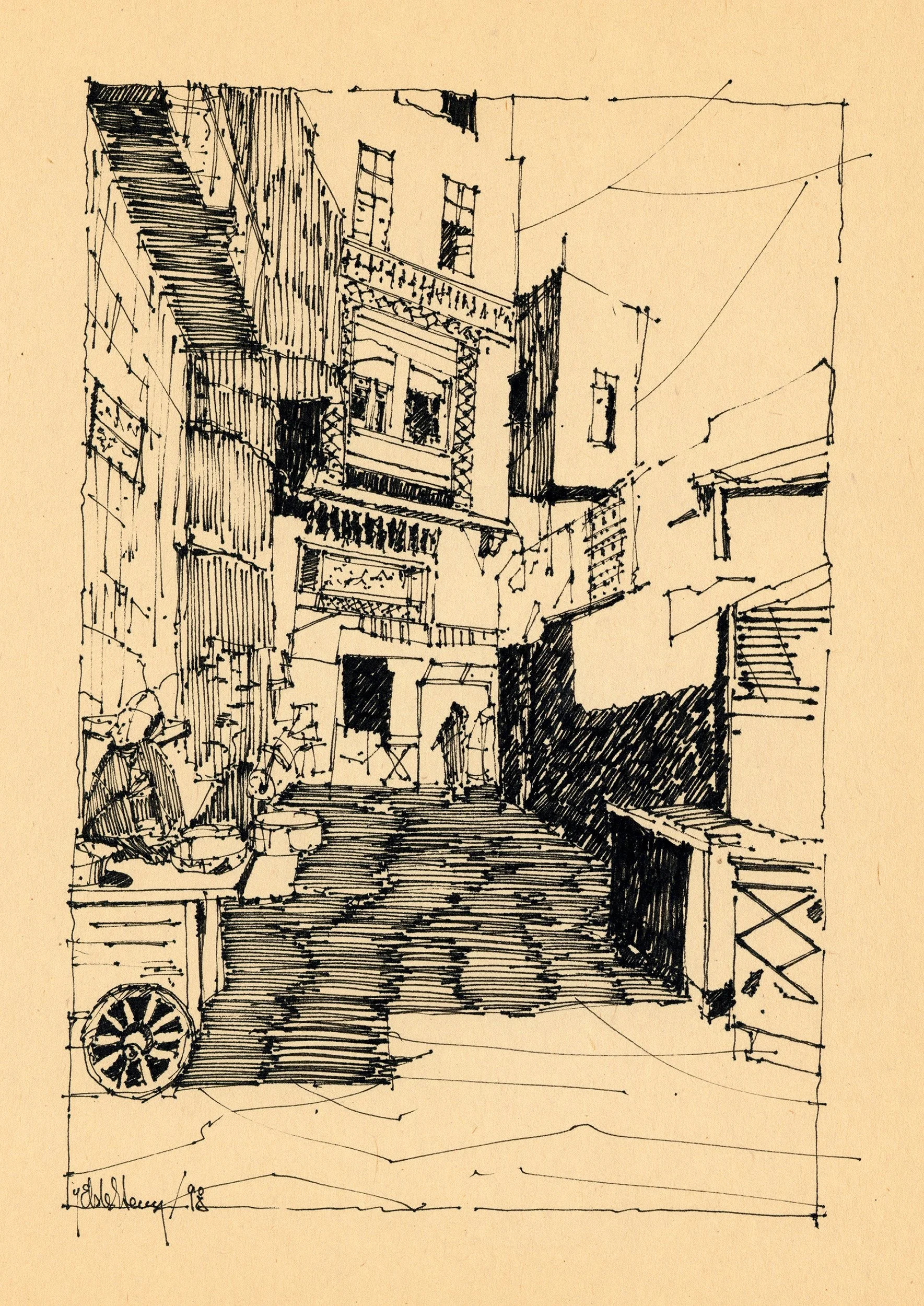

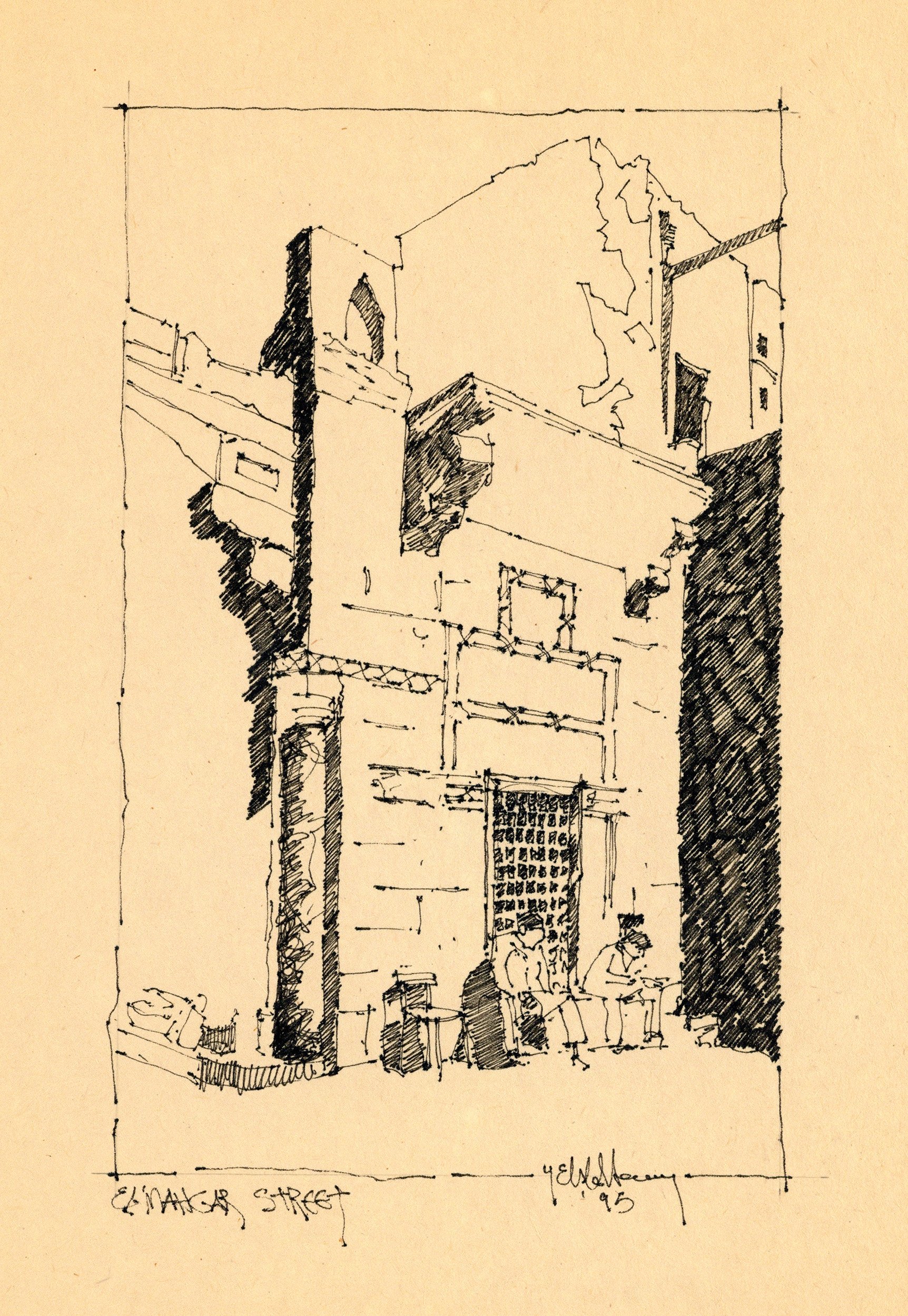

Coda: Cairo as Palimpsest

Building on the cinematic and literary sections that precede it, this section extends the idea that cities are remembered not through grand narratives but through fragments, atmospheres, and everyday spaces. Just as films and novels reveal how streets, buildings, and routines become vessels of memory and emotion, Cairo is approached here as a fragile palimpsest shaped by use, loss, and sensory recall. Drawing on Andreas Huyssen’s reflections on memory and forgetting, the city is shown to oscillate between erasure and over-monumentalization, where official preservation can obscure lived life as much as demolition. Against this, My Cairo assembles cafés, alleys, cinemas, and unremarkable corners into a personal archive—an act of remembering that aligns with the cinematic and literary traditions explored earlier, treating the city as an emotional, lived text rather than a fixed map.