Adrift on the Nile: A Cairo Walk

OPENING MONOLOGUE

Emad Hamdy, playing a destitute teacher walking the streets of downtown Cairo while we hear his inner monologue. All the while surrounded by all sorts of people, busy traffic, and historic as well as modernist downtown buildings. He is drifting aimlessly.

Scene 1:

“ Fashionable clothes. A collection.

Why are they doing this to themselves?

They are right

When the wife dresses up for her husband at home, isn’t she in his face all day?

It’s better if she makes herself pretty outside

So how do they buy all this stuff?

Yes, they must have a lot of money

Damn the money

Do they really pilfer money or do they steal

Or or …

Yes, the salaries must be high

And people don’t know what to do with the money

So they are forced to squander it

Will he have all this wealth and enjoys it by himself? No he must let people enjoy it as well so he is not selfish

Of course … an honorable man!

Scene 2:

Walks to a vendor on the Nile corniche

Salam Alaikom … Wa alaikom al Salam

Is Master (Mo’allim) Abu Sria’a around? … Look for him downstairs

Walks to the gate leading to a Nile boat. Then he is seen smoking hashish from a pipe while gazing across the Nile

Scene 3:

We are in Tahrir Square. Our protagonist is walking next to a construction crew, then we see him back again walking in the streets of downtown Cairo surrounded by pedestrians while he is walking aimlessly, drifting, consumed by his own thoughts and random reflections:

What they fill in they excavate again

What they pave they once again demolish

One time because of electricity the other for water pipes and another time for phone cables and one time for sewage

… oh what happens in this world oh what happens (a play on the Arabic where the word sewage (magari) can also mean what happens)

Why didn’t they excavate all at once?

Yeah, when they meet a lot, and plan a lot, then they must dig a lot

What’s wrong with change … what’s wrong with reports

Reports are written like that … not because the general director is drunk

When the medicine is available and beds are available why are reports written?

Don’t they say that medicines are available?

So where are they?

Pharmacies … that’s it

Instead of writing reports let’s ask at pharmacies

Does the government have nothing else to do except reports

Everyone who wants to absolve himself from responsibility writes a report

So what will we do with all these reports?

Yeah, the wisdom here is that as long we are all writing these reports we will need paper … then paper factories will work … and when there are too many reports we will burn them … matches factories will work … and when we burn the reports our clothes will ignite … then clothes factories will work …

What they intend to happen is to be self sufficient

Ya Salam (Oh Yeah!)

ADRIFT ON THE NILE: A CAIRO WALK

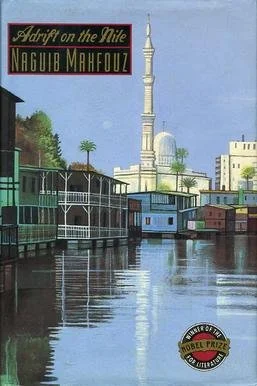

In the opening scene of Adrift on the Nile (1971), adapted from Naguib Mahfouz’s novel, we follow a man who walks without destination through downtown Cairo. He is a schoolteacher, played by Emad Hamdy, numbed by hashish and by disillusionment, drifting through crowds, traffic, shopfronts, construction sites, and the Corniche. What we hear is not dialogue but an inner monologue—fragmented, ironic, cynical, at times absurd—unfolding against the relentless movement of the city. Cairo appears here not as a coherent whole but as a sequence of encounters, irritations, observations, and interruptions. It is a city experienced from within the mind as much as from the street.

Mahfouz’s brilliance lies in how he turns urban movement into psychological drift. The protagonist does not engage the city; he absorbs it passively, filtering it through sarcasm and exhaustion. Fashionable clothes, money, bureaucracy, endless construction, reports that replace action—these are not simply social critiques but symptoms of a deeper malaise. The city becomes a looping system: digging and refilling, writing and burning reports, producing work in order to justify work. Progress exists, but it goes nowhere. The humor is dark, the logic circular, and yet the observations feel uncannily precise. Cairo here is alive, noisy, crowded—and profoundly alienating.

This mode of moving through the city resonates deeply with my own experience of Cairo. Like Mahfouz’s protagonist, I came to know the city not as a continuous map but as a succession of fragments: Downtown streets walked without purpose, sudden detours, overheard conversations, moments of irritation and delight, places encountered repeatedly yet never fully mastered. What stays with you are not monuments or grand narratives, but rhythms, contradictions, and small absurdities—the sense that the city is always in motion, always being repaired, undone, and redone.

The film’s opening scenes—Tahrir Square, construction crews, the Corniche, the transition from street to Nile boat—mirror the way Cairo reveals itself through movement rather than destination. You drift, you pause, you observe, you retreat. Meaning emerges not from arrival but from wandering. This is precisely the logic that underpins My Cairo. Like Mahfouz’s inner monologue, my project does not aim to present a complete or authoritative portrait of the city. Instead, it embraces subjectivity, memory, and lived experience: a personal psychogeography shaped by repetition, habit, and return.

In this sense, Adrift on the Nile offers more than a cinematic reference; it provides a framework for understanding Cairo as a city that is felt before it is understood. A city where critique and affection coexist, where humor masks despair, and where drifting becomes a way of coping with excess—of people, of systems, of contradictions. Mahfouz’s Cairo is not so distant from my own: fragmented, intimate, frustrating, magnetic. A city you never fully grasp, but one that stays with you long after you stop walking its streets.